The other story from the blog of Peaceful Prairie Sanctuary which inspired Clarence and Luca’s story is that of Libby and Louie. You might wonder why, because Libby and Louie are chickens not turkeys. And Libby and Louie are devoted partners, not siblings. But the story of their devotion to each other, beautifully articulated by Joanna Lucas again, is the perfect illustration of the love felt between two individuals, whatever their species, the reliance they have on each other and the place they fill in each other’s hearts which cannot be filled by anyone else.

To all those who have said that animals live by instinct alone; that they don’t think and feel as we do; that they don’t have relationships like we do, I say read Libby and Louie’s story and then think again:

Libby’s thoughts were silent. Silence was her nature, her disposition, her remedy, her talent, her power, her gift, and her pleasure. She looked at the world in soundless wonder – her thoughts, streaming and darting, swelling and swarming in the dark pools of her eyes – and filled it with the hush of her mind.

In the blush of her first weeks at the sanctuary, when everything astonished her – the open sky, the endless fields, the scent of rain, the feel of straw underfoot – we thought we heard her voice a few times: small, joyful cries coming out of nowhere, seemingly formed out of thin air, the musical friction of invisible particles, not the product of straining, vibrating, trembling vocal chords, but a sound of pure joy coming from the heart of life itself. But, after she paired up with Louie and became his sole partner, Libby turned so completely quiet, that we began to wonder if the voice we had heard in the beginning was truly hers.

Louie’s delight in the sound and functioning of his own magnificent voice, his pleasure in putting sound faces on everything – their finds and failures, their contentments and complaints, their yearnings and fears, their joys and hopes, the major, minor or minute events of their daily lives together – gave Libby the improbable ability of being heard without making a sound. For the first time in her life, she could enjoy the bliss of silence and the full power of voice at the same time. Her thoughts, her needs, her feelings, her pleasures and displeasures, were all there – perfectly voiced, perfectly formed, perfectly delivered in Louie’s utterings – each experience, captured in the jewel of a flawlessly pitched note. And in these notes, you could hear the developing musical portrait of Libby’s inner happenings.

There was the sighed coo for Libby’s request to slide under his wing, the raspy hiss for her alarm at OJ, the “killer” cat’s approach, the purred hum for her pleasure in dustbathing, the bubbling trill for her enjoyment in eating pumpkin seeds straight out of the pumpkin’s cool core on a summer day, the grinding creak for her tiredness, the rusty grumble for her achy joints.

There was the growing vocabulary of songs used to voice their shared moments of delight – the lucky find of the treasure trove hidden in a compost pile, discovered by Libby and dug out with Louie’s help to reveal a feast of riches to taste, eat, explore, investigate or play with; or the gift of walking side by side into the morning sun and greeting a new day together; or the adventure of sneaking into the pig barn and chasing the flies that landed on the backs of the slumbering giants.

Occasionally, there were the soundbursts for their shared moments of displeasure, hurt, sadness, fear, or downright panic, such as the time when Libby got accidentally locked in a barn that was being cleaned and Louie, distressed at the sudden separation, paced frantically up and down the narrow path on the other side of the closed door, crowing his alarm, crying his pleas, clucking his commands, flapping his wings, showering us with a spray of fervid whistles, following us around, then running back to the barn door, clacking at it, knocking on it, then running back to us, whirring his wings, stomping his feet, tapping the ground with his beak, staring intently, and generally communicating Libby’s predicament in every “language” available to him: sound, movement, gaze, color, and certainly scent too.

But, for all of their panache, Louie’s most spectacular acts of voice were not his magnificently crafted and projected vocal announcements but his quiet acts of allegiance, his tacit acts of devotion, his daily acts of restraint. The things he did not do.

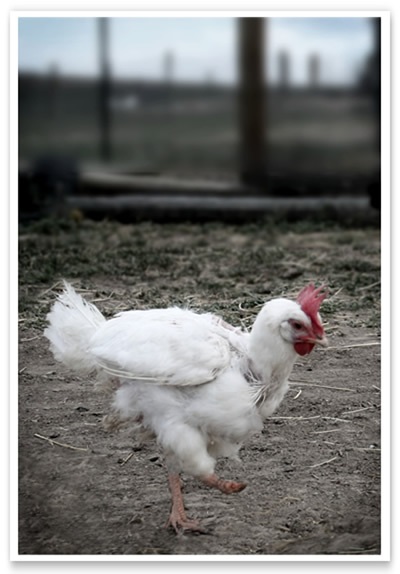

There was the silent song of giving up his treasured roost in the rafters, his nest in the sky where he had bunked every night of his years before Libby, the space where he felt safest surrendering to sleep, strongest entering the night. Happiest. The spot closest to the clouds. His personal Olympus. But, in her lameness, Libby couldn’t join him there. She managed to climb next to him a few times but, with only one foot to grip the perch, [she had lost her right foot to the wire floor of the “cage-free” egg farm from which she was rescued] she kept losing her balance and fell to the ground and, after a while, she stopped trying and just stayed there, grounded, anchored to the earth. So Louie quietly descended from his blue yonder and settled next to her in her terrestrial roost – a long, narrow tent created by a leaning plywood board – and he slept near the entrance, exposing himself to the intrusions of curious goats, wandering cats and restless geese, the better to protect Libby from them.

There was the soundless song of limiting the sport of his summer days to fewer and fewer hours when the stiffness in Libby’s stump increased with age, and the effort of following Louie in the fields, hobbling and wobbling behind him, turned from tiring to exhausting in fewer and fewer steps, and she started to retire to their nest earlier and earlier in the day. At first, she was able to make it till 6 in the evening, but then 6 became 5, and 5 became 4, and then it was barely 3 in the glorious middle of a summer day when she felt too weary to go on. The day was still in its full splendor, there was still so much more of its gift to explore and experience, and there was still so much energy and curiosity left in Louie to explore with, but Libby was tired, and she had to go to her tent under the plywood plank, and rest her aching joints. And Louie followed. With Libby gone from the dazzling heart of the summer day, the night came early for both of them.

Then there was the tacit song of forfeiting his foraging expeditions and his place in the larger sanctuary community only to be with her. When Libby’s advancing age, added to the constant burden of her lameness, forced her to not only shorten her travels with Louie, but end them altogether, and when her increased frailness forced her to seek a more controlled environment than their plywood tent in the barn, she retired to the small, quiet refuge of the House. And Louie followed her there, too, even though he still enjoyed the wide open spaces, the wilder outdoors, the hustle and bustle of bunking in the barn. But Libby needed the extra comfort of the smaller, warmer, more predictable space inside the House and, even though Louie did not, he followed her anyway. And, when she started to spend more and more time indoors, curtailing her already brief outings, Louie did too.

And there they were. Just the two of them in the world. A monogamous couple in a species where monogamy is the exception. Determined to stay together even though their union created more problems than it solved, increased their burdens more than it eased them, and thwarted their instincts more than it fulfilled them.

It would have been easier and more “natural” for Louie to be in charge of a group of hens, like all the other roosters, but he ignored everyone except Libby. He paid no attention to the fluffy gray hen, the fiery blonde hen, the dreamy red hen, the sweet black hen dawdling in her downy pantaloons, or any of the 100 snow-white hens who, to our dim perceptions, looked exactly like Libby. Louie, the most resplendently bedecked and befeathered rooster of the sanctuary, remained devoted only to Libby – scrawny body, scraggly feathers, missing foot, hobbled gait and all. It’s true that, with our dull senses, we couldn’t grasp a fraction of what he saw in her because we can’t see, smell, hear, touch, taste, sense a scintilla of the sights, scents, sounds, textures, and tastes he does. But, even if we could see Libby in all her glory, it would still be clear that it wasn’t her physical attributes that enraptured Louie. If he sought her as his one and only companion, if he protected that union from all intrusions, it wasn’t because of her physique but because of her presence.

It would have been easier for Libby too – so vulnerable in her stunted, lame body – to join an existing chicken family and enjoy the added comfort, cover and protection of a larger group, but she never did. She stayed with Louie, and followed him on his daily treks in the open fields, limping and gimping behind him, exhausting herself only to be near him.

What bonded them was not about practical necessities or instinctual urges – if anything, it thwarted both. Their union was about something else, a rich inner abundance that seemed to flourish in each other’s presence, and that Libby nurtured in her silence and that Louie voiced, sang out loud, celebrated, noted, catalogued, documented, expressed, praised every day of their 1,800 days together.

Except today. Today, it was Libby who “spoke” for both of them. And, this time, there was no doubt whose voice it was, or what it was saying, because it not only sounded off, it split open the sky, punctured the clouds, issued forth with such gripping force and immediacy that it stopped you dead in your tracks. It was a sound of such pure sorrow and longing, hanging there all alone, in stark and immaculate solitude, high above the din of sanctuary life, like the heart-piercing cry of an albatross. She had started to cluck barely audibly at dawn, when Louie failed to get up and lingered listlessly in their nest. She continued her plaintive murmur into the afternoon, when Louie became too weak to hold his head up and collapsed in a heap of limp feathers. And then, when we scooped him up and quarantined him into a separate room for treatment, her soft lament turned to wrenching wail.

The next morning, she was still sounding out her plea, her love, her desperation as she feverishly searched every open room in the house, then wandered out into the small front yard, then the larger back yard, and the small barns behind it. Soon, she left the house and the fenced yard and took her search to the open fields, cooing, calling, crying like a strange sky creature, using her voice as a beacon, it seemed, a sound trail for Louie to follow back to safety, and roaming farther than she had in months, stumbling and staggering on a foot and a stump, the light in her being dimming with every solitary minute, her eyes widened as if struggling to see in dark, her feathers, frayed at the edges, as though singed by the flames of an invisible fire, their sooted ends sticking out like thorns straight from the wound of her soul, her whole being looking tattered and disoriented, as if lost in a suddenly foreign world.

And, for three excruciating days, we didn’t dare hope she’d ever find him alive again. Louie was very weak, hanging to life by a thread that seemed thinner and thinner with each passing hour. He didn’t respond to the treatment we were advised to give him and, after three days of failed attempts, we were beginning to accept that there was nothing more we could do except to keep him comfortable, hydrated and quiet until the end.

But we underestimated both his strength and her determination. Libby did find her soul mate again. We don’t know how she managed to get into the locked rehab room, but she did. We were planning to reunite them later that day – going against the Veterinarian’s advice, as we sometimes do out of mercy for the animals – because it had become clear to us that Louie’s ailment was not contagious, it was “just” a bad fit of old age. But Libby beat us to it. She found her way into his room, only she knows how, and Louie found his way back to life too, seemingly at the same moment. There he was, looking up for the first time in days, life flaring in his eyes again, and there she was, huddled next to him, quietly sharing his hospital crate. And there they still are, Louie, slowly recovering, and Libby, blissfully silent again. She hasn’t moved since. She won’t leave his side now that she’s found him again, she refuses to even look away from him, as if he might disappear in one blink of her eye, as if the force of her gaze alone can keep him anchored in life.

They are both quiet now – Louie, exhausted from his ailment, regaining his strength, Libby, exhausted from her dark journey, gazing steadily at him. Both, brimming, basking in the rich silence that is so alive with voice and flowing conversation, that it glows between them like a strange treasure. And it shines.